“Lovecraftian” is a word that I wouldn’t exactly called abused, but it’s both easily recognised and a little open to interpretation.

Stygian‘s intepretation of Lovecraftian horror is almost meta. I’d call the core of Lovecraft a confrontation of reality. It’s not that the truth is gory or big or even scary. It’s that it just doesn’t fit into the human mind without shattering it. It’s not even actively malevolent. Indeed, the defining feature of a Lovecraftian monster is its sheer indifference.

It’s about how fundamentally, all humany’s ideals and beliefs and societies are inventions we cling to in order to shield us from that horror.

Stygian is basically an RPG about doing that.

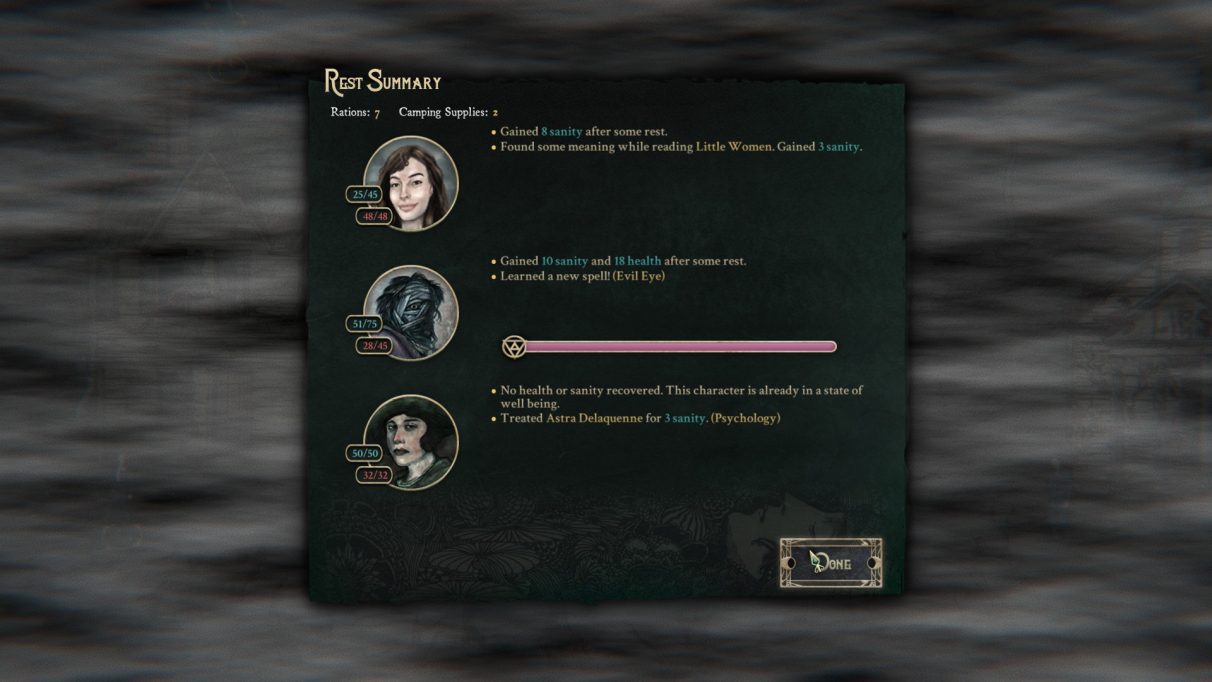

I’ve had some issues with Stygian. Combat is slow, dull, and a bit too influenced by chance. Its treatment of mental illness as traits you can spontaneously pick up while walking across a room is a bit unfortunate (although thematically it would be daft to not gradually wear your character’s mental health to nothing, and it’s somewhat refreshing that developing schizophrenia doesn’t turn you into some kind of monster or tragic figure). How and why it saves games so haphazardly is beyond me. But I’ve really enjoyed its atmosphere, and I think it communicates well a subtle, abstract part of why old HP’s less hateful work was such good horror.

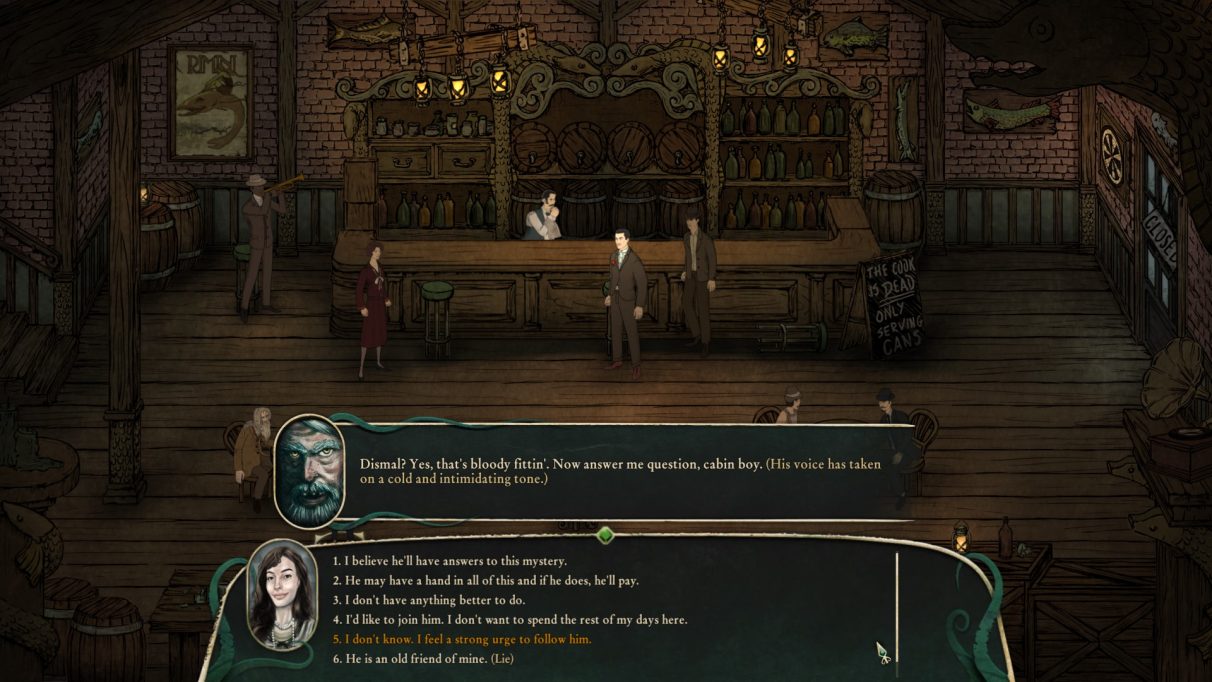

The premise is simple enough. The town of Arkham was vwomped into another dimension some time ago for unknown reasons. The survivors have settled into a surprisingly stable subsistence, although as you might imagine, between the aforementioned existential horror and plain trauma, everyone is a bit of a mess mentally. They’re also under the thumb of the Mob, which leveraged its control of the much-needed drugs and alcohol to take over pretty much undisputed. And anyone who gets really out of line, they mark for the attention of the cultists across the river.

You have an odd dream in which an ominous Rorschach-lookin’ feller, the Dismal Man, leads you out of the attic you’ve rented (using cigarettes as currency) to the steps of the old university. Naturally, when you wake up you retrace those steps, and there’s a main plot you have to follow, but Stygian isn’t just about following the main plot, per se. It’s about how you react to the whole setting. That’s broadly true in any RPG with a lot of conversation of course, but here it feels more fundamental. Character creation demands that you choose a belief system, not simply as roleplaying flavour, but to explain how you’ve endured until now.

Rationalism. Faith in the divine. Occultism. Humanism. They’re all coping mechanisms when you get down to it.

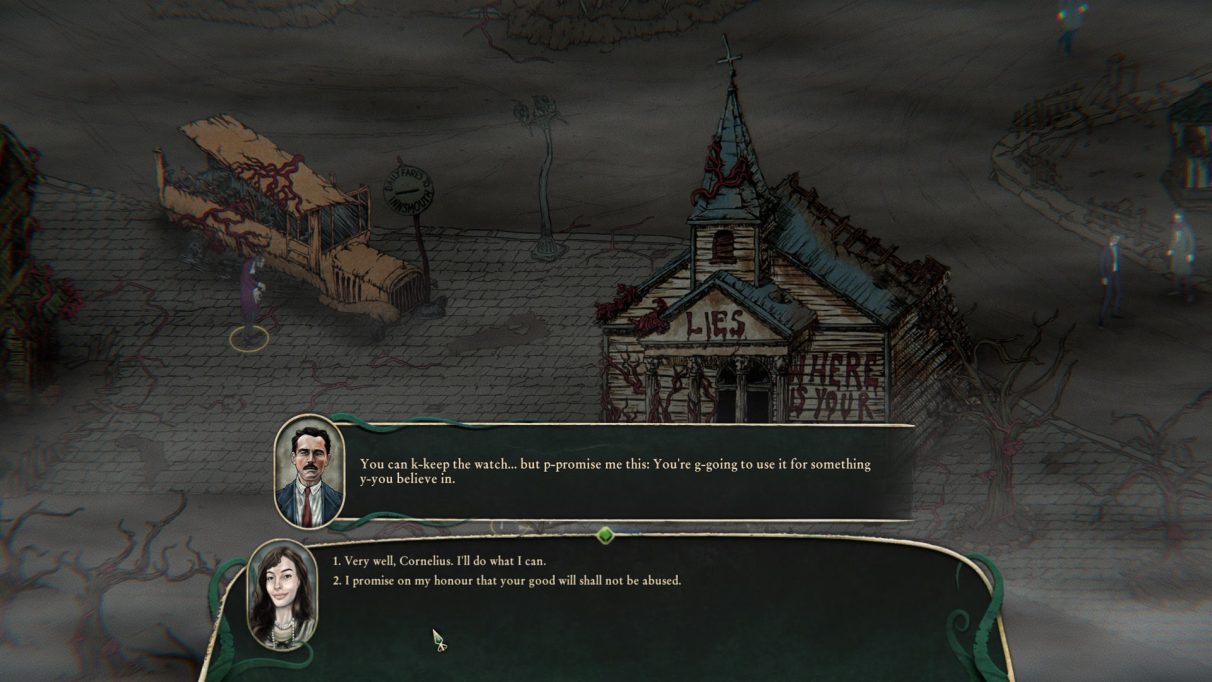

Faith and philosophy, or even just strong opinions, are commonplance in RPGs, but feel more significant here, in this setting, where it’s not just an intellectual excercise in who’s right, or philosophically comfortable. It’s precious and important – the last thing between the protagonist and the terrible void. Kindness too feels more momentous. RPGs are often wretchedly dystopic and full of people who are suspicious of generous strangers, or pathetically grateful. In Stygian, optional moments of kindness become powerful, since the enemy isn’t fascism or aliens or zombies or some generic evil, but despair. Or even reality itself.

Where other games treat this question as “if you had to choose, which of these things matters?”, Stygian asks “what keeps you anchored in this hopeless existence?”

Even nihilism is a belief of sorts in this place, a kind of armour to numb yourself and perhaps smother your conscience. And occultism too – where the easy thing with Lovecraft is to make the cult powerful, their fervour and ceremony is itself a coping system. Do the elder gods hear them? Of course not. Their rituals, their surrender to idolatry, their revelry in cruelty and madness are a mote of dust in the cosmos. Just another, particularly bloody piece of driftwood on a cold, eternal sea.

My initial surprise was that humans were still subsisting here, and not completely devoured. But it seems that the appearance of Arkham in this vast plane is a completely irrelevant event to whatever lives here. Fitting. Lovecraft’s contribution to horror was less about a big monster hating everyone than the sheer existential horror of scale. Not that the monsters are big and many, but that we are finite in an infinite reality. And it’s one thing to know that intellectually, but to truly perceive it is like being force-fed a continent.

Its defining moment comes after a few hours, which was when someone finally asked why I sought the Dismal Man. The reply options ranged from blaming and attempting to punish him for causing this, to seeking answers, to a basic “iono”. I don’t know, but suspect that ultimately, the plot will simply be what it is, and no answers will resolve anything. Perhaps you’ll kill him. Perhaps you’ll have a long talk and leave. Perhaps you’ll join, or become him. I think it more likely that he will simply happen, and the player character will have to make their own peace with that, or not.

I think I can live with that.