Strategy games are, as everyone knows, much like moving house. Whether it’s your first, daunting one and you don’t yet know that the whole “most stressful thing in life” line is a total lie, or you stopped counting house moves after your 15th, there’s one obstacle that never stops getting in the way: the deposit.

You know you can pay it, theoretically. You could gather together the energy and focus it takes. It is not beyond you to learn how a new game works and take the time to situate yourself within its world. But doing it all at once? Right now? Ach. Now you’re asking.

That’s the deposit. And it prevents you from playing games you’d love.

You’ve already overcome the earlier obstacle, that period when you’re staring at a list of appealing games, paralysed with indecision. You’ve even hurdled the bit where you start it up (turning down the music, disabling motion blur, fixing the mouse sensitivity, muting all voice chat, etc, etc), but then you realise you’ll now have to learn how everything in it works. Ugh.

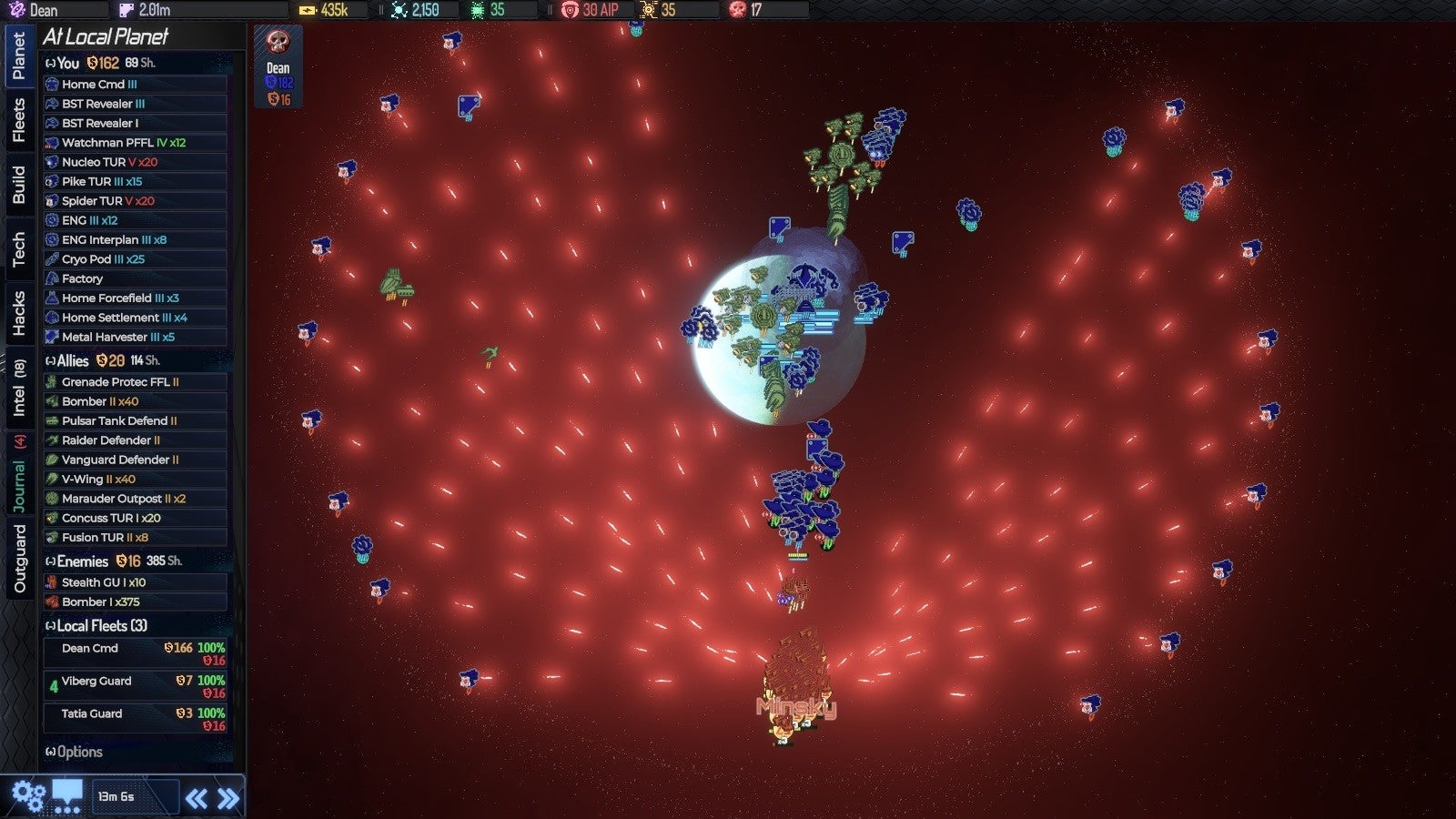

Take a game like Grand Tactician Colon The Civil War (1861-1865, in America, Specifically The Region Now Known As The United States). It’s a game I’m fascinated and excited by but still haven’t grasped enough to consider the deposit even close to paid. Or AI War II, a game that’s actually more manageable by design than the original and has begged me to play it with piteous eyes for nearly two years. I want to play you more, AI War 2. I liked you but I couldn’t quite meet the deposit. I’m sorry.

Sometimes it’s not even an unfamiliar game. Battletech has been burning a hole in my hard drive for over a year, and I’ve already played it enough that I’d relearn its ways in no time. But there’s still that setup cost. Either I’ll have to rebuild from the beginning again, or be cast adrift in a saved game whose context and plans are long forgotten, the significance of each mech, their loadouts and formations lost.

Strategy games need momentum, and it’s their strength and curse. They’re (mostly) hefty machines, and a good one will pull you along with sheer inertia once they get out of gear in a way that few other genres can. And while I can’t tell you how to steer them all, I’ve learned a few tricks in my time that could act as an ignition sequence to help you get started on the deposit in this increasingly tortured metaphor. You weren’t born knowing how to use a mouse or phone or controller, and even complex games are usually a lot less demanding than they look.

Put it this way: as a child, I figured out how to play many 90s strategy games without a manual. You are almost definitely smarter than a child. You can do this. And here are some methods to help.

1. Learn to lose

This can be tricky if you easily form attachments with your in-game towns or narratives. Shadow Empire‘s brilliant hook of generating entire planets from base physical principles was double edged: sure, it meant that I was already curious enough about the world I’d created to push through the deposit of learning its dense simulations. But it also meant that losing a game effectively destroyed that whole world along with my chances of ruling over it. And there really is no better way to learn a game that esoteric than burning world after world, while occasionally alt-tabbing to its manual to answer specific questions.

But it’s not the best place to start out. And while Dwarf Fortress famously treats “losing is fun” as an unofficial motto, it’s far too time-intensive for a starting point, even if its in-progress UI overhaul dislumpens its worst parts. Instead, I’d colour outside the column a bit here, and suggest Hunt Colon Showdown as a guide. When your character dies, they’re gone forever, as is any gear they’re carrying. But there are always more recruits and guns. You will learn to lose. Take that lesson in, and the prospect of watching your kobolds die out over and over in Conquest of Elysium 5 becomes much more instructive.

2. Set goals

This is more of an issue with open-ended sandboxy deals, or grand strategies with a distant, overwhelming goal. Fight World War Two? Organise the biggest mess in human history? Oh sure, I’ll start that right now mate, deffo. But it can be a useful approach in any strategy game. When I first played XCOM Apocalypse with a cousin, we were very pleased with ourselves for figuring out how to get a hovercar to go where we wanted. It can be as small as that, to establish a foothold that wears down your brain’s resistance to spending more time and energy on a new game. Who says the sunk cost fallacy can’t work for you?

When you’re new to the game, don’t focus on winning or even understanding everything. Set a humbler goal. Try to find every AI capital in a 4X. Hold your front line in a wargame. Get your literacy rate to 90 in that city builder. Depending on the difficulty and complexity of the particular game, it can be a direct learning goal. “In this playthrough, I’m going to figure out how supply lines work”, say. My humble village in Workers & Resources started as an attempt to understand population and agriculture at a scale I understood, and moved on to managing vehicles, then the entire production web. That became one of my favourite towns in a game ever, whereas I barely remember and was mostly frustrated by the ones where I’d tried to learn everything all at once.

This approach means that perfectionism (and perhaps a little egotism. I’m not exactly a sore loser, but I’m not a great one either) won’t hold you back. It’s okay if your empire will definitely fall to the Zorblavians, since you were only here to learn how the shipyards worked anyway. The pressure is less, you’ve invested less, and if you succeed, you get to choose to bow out on your own terms, or keep going and take yourself a little further by degrees. You’ll learn a lot more, and stress yourself out a lot less, if you don’t try to learn it all at once.

3. Play against type

we all say we’re going to do this. This time I’ll be warlike. This time I’ll spurn the universally superior 4x approach of going full research nerd, and raise a civilisation of merchants instead. This time I won’t deliberately antagonise England. These resolutions often fall apart, but if you’re disciplined, and set out explicitly to yourself what path you’ll take for this playthrough before it starts, and refer back to it often, you’ll stick to the game more consistently because you have an idea.

While it might sound more daunting, again, it actually takes away pressure, and gives you a feeling of control. If you fail, you can blame your daft experiment, not your lack of experience. Experience which you now have, along with a better idea of what is and isn’t possible in the game. I may not have survived for long in Starcraft using only Vultures, but it taught me many ways to confound and weaken people with their mines.

You can even just play it plain wrong on purpose. When I attempted to learn Space Engineers properly and sensibly, I got nowhere. But when I decided I would work my way up from a crashlanded buffoon to a mighty space pirate, I … took two weeks to build a crap moon buggy that flips over three times when it hits a pebble, and sears your shoulder flesh to the bone if you turn left. They can’t all be winners. But I had more fun failing my way to that purple buggy than I would have by trying to be sensible or competent, and consequently, the deposit shrank before me. And as a bonus, if you go in with a daft plan you can sometimes find a whole new dimension even to a game you thought you knew well. Just ask the Red Paper clan.

4. Become the teacher

I’ve learned almost several things in my life, perhaps the most potent one being that the best way to understand something is to explain it to someone else. This forces you to examine it differently, and clarify what you DO know, which sheds light on what you don’t in an almost socratic way.

It also means that even the slightest knowledge makes you a relative authority, and that brings confidence. While learning EVE Online I briefly mentored a few even newer players, and having to explicitly type out how salvaging fit into industry is how I came to consciously understand it.

The first one of you I ever met in real life was at the Rezzed afterparty, where I was terrified and alone and knew nobody. But the one of you I met (hello Chris!) was from a whole other country and even more nervous, and thus I immediately became a walking Who’s Who, able to introduce him to Adam and Alice and Graham and about 6 other people I’d literally never met. Neither Dunning or Kruger anticipated that their work would one day be used to our advantage. Well, I assume not anyway. I don’t know much about them to be honest.

Unfortunately, Reader Chris is probably too busy to listen to each of you you talk about every new game you ever play, so you might need to kidnap a friend to forcibly educate, but it’s probably safer to write yourself a short email about the game as you try to figure it out. Be warned that this method carries a very slight, but non-zero risk of accidentally becoming a games critic.

5. Watch this series of video tutorials

Go directly to hell.