Petrol stations might not be the most natural setting for pondering life’s biggest questions, but the ones in Flat Eye, the next game from the makers of detective taxi-me-do Night Call, aren’t your ordinary rest stops. As well as a convenient place to relieve yourself and top up on snacks, these futuristic service stations also house cosmetic surgery bots, operation tables, teleportation booths and more – and they’re all overseen by a powerful AI trying to find the best possible future for the human race. As the station’s head clerk, you’ll debate the ethics of eternal youth and end of life care, while also making sure your station has enough power, stocked shelves and a happy customer base. It’s certainly an intriguing combo compared to other management games out there right now, so I sat down with director Laurent Victorino and writer Antony Jauneaud to find out more.

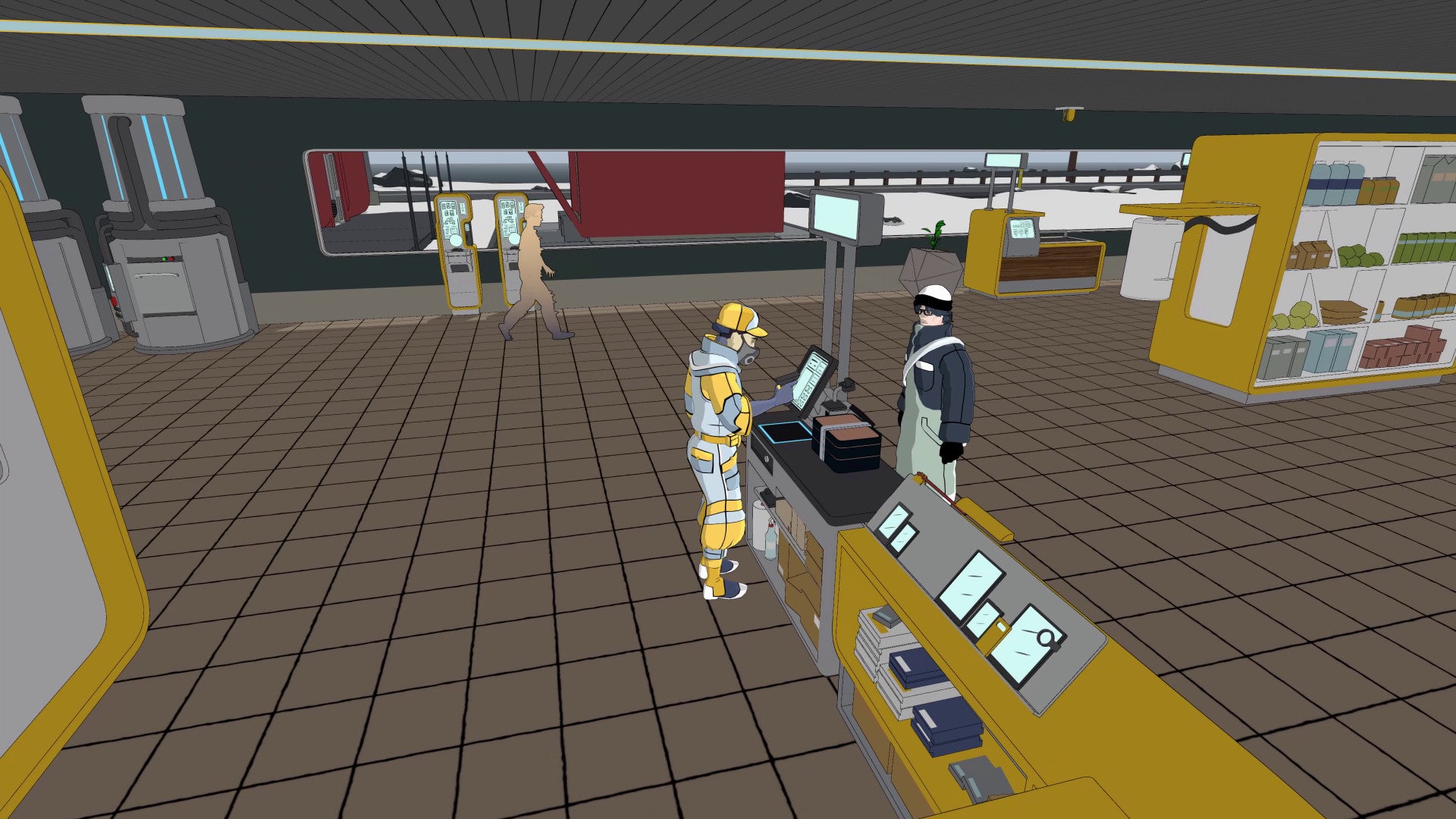

“We really wanted to find an interesting mix of management and narrative in the gameplay,” Jauneaud tells me. “Our main inspirations were, of course, games like Theme Hospital and Dungeon Keeper. We also wanted to make something that had a bit more, let’s say, meaningful story to tell, like we did with Night Call, to share with players slices of life and have them meet characters that they’d never heard about. It’s really important that our games are about meeting people you wouldn’t in real life. So that’s what we wanted to do with the service station. It’s a place where people stop whether they’re rich or poor, sometimes even if they don’t have a car, they will stop there, and for us it was the perfect setting for the game.”

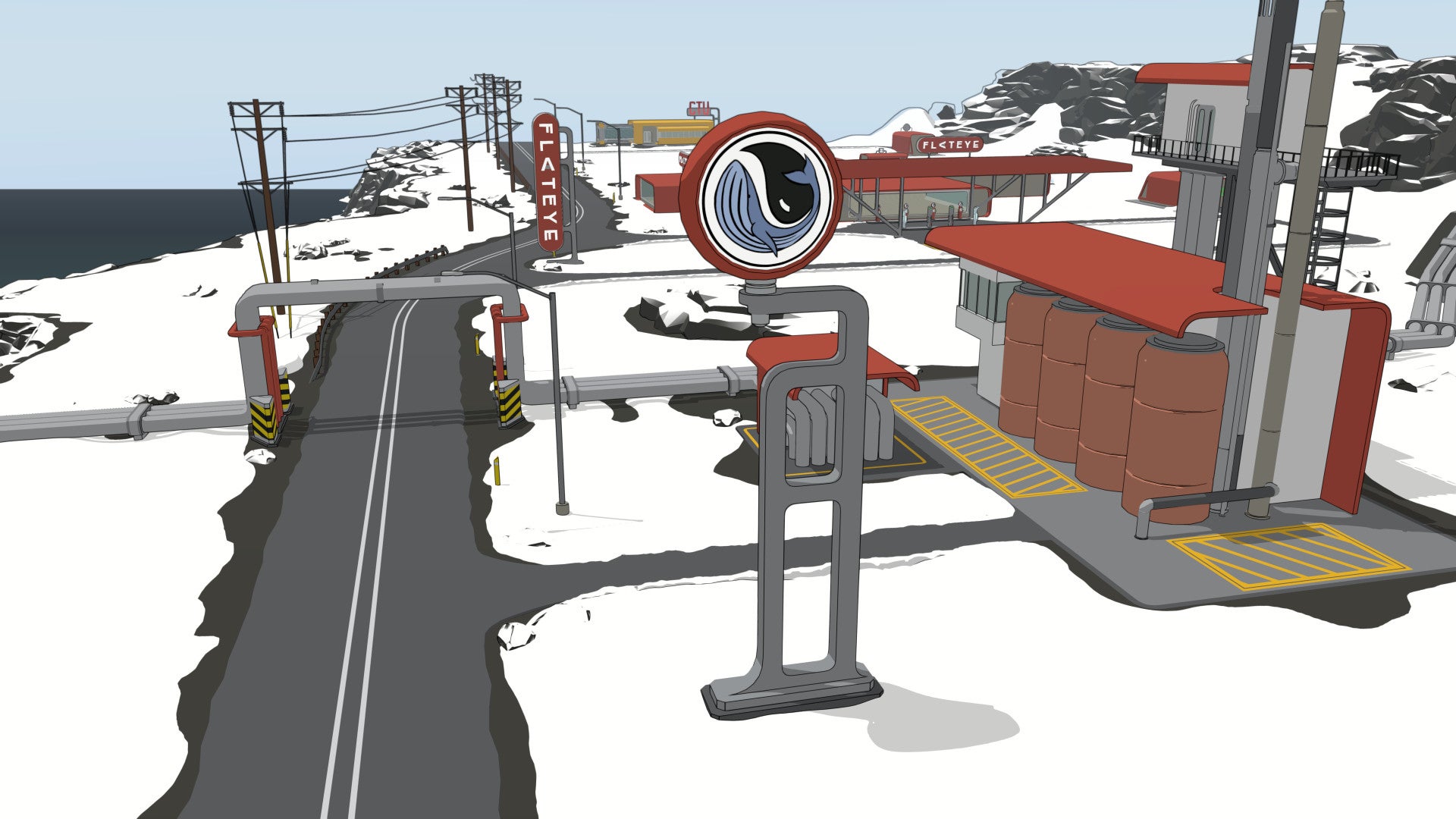

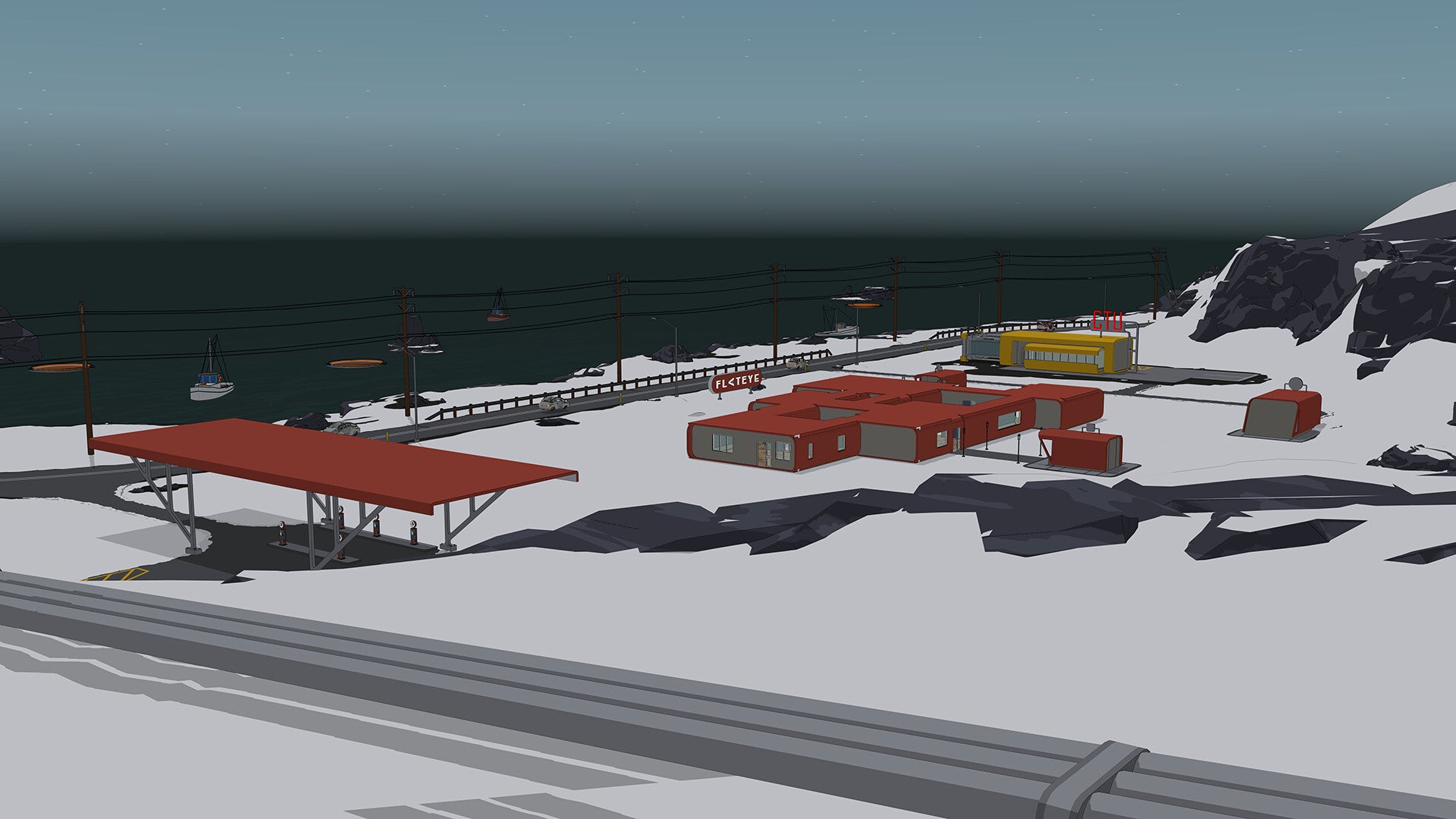

The station you’ll be running is located in Iceland, and over the course of the game you’ll be kitting it out with various Eye Life technology modules, as provided by the titular Flat Eye Corporation, a Google/Amazon-sized tech firm who may or may not be a little bit evil in their voracious quest for data. You’ll start small in Flat Eye, first installing your all-important EyeCore module that houses the game’s guiding artificial intelligence, before moving on to more practical additions like geo-pumps to satisfy your station’s energy needs, automatic cash registers and smart toilets. All of these need to be connected to the EyeCore in order to function, and managing your store’s energy resources will form “a big part of the game,” says Jauneaud. However, he’s also keen to stress that players won’t be penalized if something’s not working properly.

“What we want is that all our features are simple enough so you can have fun with them, but they’re not too complex that they’re overwhelming,” he says. “We wanted to make an experience that was approachable by a lot of different people, because often, now especially, strategy games and management games are extremely complex. We’re going to have different difficulty modes, but we’re also going to make an experience that is very chilled, not only in its looks, but also in the music, the gameplay and everything else.”

Indeed, no sooner have these words left Jaunaeud’s mouth than Victorino, who’s on game playing duties during my remote demo session, runs out of money. “Are we going to lose this game now?” Jauneaud asks. “Just after I said it was un-losable?”

Fortunately, Victorino has just spent our last wodge of cash on a smart toilet, whose by-products happen to be data and bio-matter. “What’s going to happen soon is that we’ll be able to produce a food machine that’s going to then sell things like dishes and hot dogs and sandwiches to people, and you will be able to connect the toilet to the food machine because, well, bio-matter!” Jauneaud explains.

“It wouldn’t be a management game without [graphs].”

There’s a similarly laidback approach to the game’s end-of-day graphs and stats. They’re there because “it wouldn’t be a management game without it,” Jauneaud tells me, but they don’t have any real bearing on your ‘success’ as a station clerk. After all, it’s the AI who’s the real brains of the outfit here. You’re just “an ant” and “a little cog in a large machine,” Jauneaud says, so it makes sense that you’re not directly responsible for the station’s financial wellbeing.

It’s a feeling that was partially inspired by the team’s previous experiences working in retail, according to Jauneaud, but it also stems from the team at Monkey Moon’s desire to make a game where “you can’t have a game over.” The AI in charge of your station, for example, is “trying to find a way of using the store as a way to test potential futures until she can find the best option for humanity to survive in the future,” Jauneaud tells me. “So to do that, she’s not going to let you have a game over, of course.”

As my demo session goes on, though, it becomes increasingly clear that the removal of any kind of fail state isn’t just about catering to different difficulty levels. It also speaks to a wider pre-occupation with corporate structures and responsibilities, and the ease with which technology can both improve our lives and, inevitably, run away from us. Indeed, as you gain access to more advanced modules in Flat Eye’s tech tree, you’ll start to encounter named characters who you’ll be able to have Night Call-style dialogues with. These tech-focused conversations take place in a special, dedicated environment known as The Bubble, where store operations are suspended for a time so you can focus on the dialogue. You don’t control the clerk directly in these situations, Jauneaud tells me – you’re merely suggesting what they might say to these “premium customers” – but the way you conduct the conversation will change what each character thinks of the technology module they’re attempting to propose, and whether they’d like to go through with their respective procedures.

To illustrate this point, there was a character called Hal in my demo who wanted our clerk to offer a machine that eradicates signs of ageing. In the final game, we would have spoken to Hal several times before this point, much like how Night Call’s taxi stories played out over multiple pick-ups, and choices we made in previous conversations will have a bearing on how these final encounters play out. However, while Hal puts forward a good argument, our guiding AI isn’t best pleased. Indeed, she’s worried that allowing this machine to be created now will effectively put humanity on a path where the elite have access to eternal life, and after a lot of thoughtful discussion weighing up the pros and cons, she decides to nip this future in the bud before it gets out of hand.

Most of the premium customer conversations you’ll have in Flat Eye will end in a similar fashion, Jauneaud tells me, but eventually you’ll find a few where you’ll really have to decide whether you want to pursue it or not.

“We want to make sure that people don’t have to restart the game every time they reach an ending, so we have what we call outcomes, which are futures that the AI is able to predict right away and say, ‘This is not the right way, I know this is not a viable future, so I’m going to cancel it,’” he continues. “As you progress through the game, you will unlock technologies and modules and meet customers that will offer you actual, potential, viable futures, and we have between three and five [out of around 20 possible outcomes] that are going to be for the player to choose whether they want to live in a certain kind of future. Those are like end-game endings.”

Jauneaud and Victorino expect it will take around ten hours before you encounter one of these endings, but they say the team have been careful to make sure that “technology is not shown in the game as good or bad,” which will hopefully avoid obvious, Black Mirror-style pitfalls we’ll be able to spot from a mile away. “It’s really how people use it,” Jauneaud adds, citing Black Mirror as a reference, but also emphasizing that they “wanted to show you can also have wholesome, nice, interesting stories using technology” that aren’t always “very negative”.

“I think the goal for me and the team is to tell the story about how we get to the utopia we are all praying for,” he says. “To get there, we have to make sacrifices, we have to test stuff, we have to fail and we have to succeed. It’s not going to happen in one day, and to me the whole game is about that. It’s about how we have options and we’ve got to pick the right one and how are we going to do it. Personally, I feel like technology is seen as a saviour for a lot of people and it’s a big, big mistake. Technology is not going to save us. It’s really how we are managing technology and how we are using it.”

“Personally, I feel like technology is seen as a saviour for a lot of people and it’s a big, big mistake. Technology is not going to save us.”

Indeed, a lot of the tech modules you’ll find in Flat Eye are “based on actual technologies, or technologies that exist in a certain way,” says Jauneaud. The dawn of our second day unlocks the SurgeryLife machine, for example, which, as the name implies, allows customers to undergo complex operations in the blink of an eye. There’s also the FutureLife machine, where customers can get predictions on how to handle the rest of their day.

“Some of the more farfetched technology, of course, is more inspired by science fiction, but when we started to work on the project, we had a list of modules that had to be in the game. We wanted to have a tech tree that felt logical, so we started with the far-fetched technology that we wanted at the end of the game, and then we thought about the technology that would come just before. So before we can teleport people, we would probably be able to teleport objects, and to have objects, you’d probably need to print objects. That’s how our tech tree works. [But] as game development is ending – we’re hoping to release the game in 2022 – the more we wait, the more outdated our game is going to be. It’s starting to become very, very problematic for us, so we have to hurry up now.”

One of these problematic elements is the game’s inclusion of “suicide booths”. When Monkey Moon first started work on the game in 2019 after finishing Night Call, it was a concept that was “in discussion in some countries where they have assisted deaths,” Jauneaud tells me, but time has since caught up with them. “Right now, in Switzerland, a couple of months ago, they built an actual suicide booth, and we really need to hurry up, or we’re going to look old.”

Flat Eye’s release date has since been confirmed as October 17th in the months since, but Jauneaud is referencing the 3D-printed Sarco pods created by former Australian doctor Philip Nitschke – something that’s undoubtedly going to be a subject not all players will want to engage in. Jauneaud stresses there will be in-game content warnings before these dialogues take place, “to make sure we prepare players for modules that will include heavy topics,” but he also feels it’s important for games to have these types of conversations in them rather than shying away from them.

“Honestly, this is my view, this is probably not the game’s view, [but] we live in an age where technology is moving whether we want it to or not,” says Jauneaud. “Do I want a guy to build a tunnel under Los Angeles? Probably not, but I’m not going to do anything about it. So I think those topics have to be discussed, they have to be part of the discussion, otherwise technology is going to overcome us. Technology is going to win without our input. As a French person, I think it should be normal. Probably not in a service station, obviously, but you will see in the game, you cannot just come to the module and get in it and die. That’s not how it works, you have to go through a process, [and] we address these issues in the game.”

In fact, there’s another rival company in the game called Hibiscus “who are jealous of what Eye Life is doing,” says Victorino. “You’re going to have a lot of characters and customers complaining about the hegemony of Eye Life and all these technologies, but also competitors trying to sabotage what the company is doing. You’re in the middle of that.”

Fortunately, your “very pragmatic” AI does genuinely seem to be on the side of humanity rather than the Flat Eye corporate overlords, and I’m intrigued to see how, as Jauneaud puts it, she “[tries] to understand the world and better understand humans and why humans are so dumb and inefficient at what they’re doing” – all while they’re trying to actively destroy her.

“I hope people at the end of the game, when we try to explain what we’re trying to do and how we think about technology that, it’s a good thing, if it’s used properly. And it goes with the example that we’ve seen, with this character asking to live forever. Yeah, technology will probably offer that at some point, but is it a good idea? Should we do it just because we should? That’s the main topic of the game.”