Planet Zoo is a game where you can build your own zoo. It’s buggy, intermittently opaque, frequently saccharine, and – barring an eleventh hour miracle – it’s my undisputed game of the year. Because here’s the thing: it’s a game where you can build your own zoo. And by thunder, it delivers on that promise.

Usually, by the time I review a game – especially one as savagely time-guzzling as this one – I’m burned out on packing so many hours of play into a few days, and I’m ready to say my piece and move on. This time, my instinct is just to nod distractedly, tell you it’s good, and get back to playing. But here, for the sake of professional responsibility, is wot I think.

Like a grinning divorce lawyer, setting up a stall in a Scarborough caravan park as the rain descends for half-term week, Planet Zoo saw me coming. My first memory is of elephants in a zoo. I was obsessed with Noah’s Ark as a toddler, and went on to spend whole weekends filling the living room floor with zoos made of wooden blocks, ice cream tubs and plastic fencing. Their inhabitants – a nearly full set of the legendary Britains’ zoo animals – became so worn from use that the noses and ears came off the elephants, and the giraffes were bleached into gangly, albino nightmares.

As I grew older, the wooden blocks were replaced with graph paper, as I planned out yet more hypothetical beast accommodation, and eventually by real glass tanks, as I built a teenage menagerie of frogs, lizards, scorpions and beetles. Hell, as I type this, I’m watching an orchid mantis molt in a tank on my desk. I studied the history of zoos and aquariums in my final year at uni. I even worked in a zoo for a while, looking after the animals for the education department at London Zoo. I had the keys to the lizards and everything. So yes: I am Planet Zoo’s target market. But as when anyone comes to make a definitive statement about the thing you love, I was also bristling to be underwhelmed.

There’s elements I don’t like. It’s so bright and wholesome and world-music-section-cheery in its insistence on portraying zoos as a force for good, you can’t help but get the sense it’s protesting too much. The swaying, misery-eyed elephant in the room here is the debate over the ethics of zoos, and while I’m not having it here (go talk to Edwin), Planet Zoo plasters over the whole issue with the desperate, sweaty smile of a serial killer showing the cops their collection of Babylon 5 memorabilia to stop them finding the Torture Room.

The game’s relentlessly positive messaging also means you can’t make a shit zoo. The sad fact is, there are still zoos where suicidal tigers sit collecting mould in chainlink horror pens, and they still make a lot of money. Planet Zoo, entirely reasonably, didn’t take the hands-off, Prison Architect approach of letting you damn yourself with your own decisions. If you don’t treat the animals like lords, you’ll fail catastrophically, and even if you don’t want to do anything horrible, there’s still often a sense that you’re being strongarmed into playing according to pre-assigned values. There will be no bird holes here.

The game is also ruthlessly marketed at the awww-cute, send-me-animal-pics-to-cheer-me-up demographic, rather than at people with a less emotional fascination. The game isn’t fact-light by any means – it’s got a brilliant, 34,000 word in-game encyclopedia – but the focus is very much on tubby baby pandas. Indeed, the game’s bestiary focuses almost entirely on large mammals – or charismatic megafauna, as they’re known in the business. Of the seventy-odd “habitat” animals in the game (that is, the ones you can design enclosures for) just six are reptiles, and there are a measly three birds. Enclosures for flying creatures aren’t a thing, and there’s not a single fish in the game.

There are 23 smaller animals in the game, including nine more reptiles, three amphibians and eleven invertebrates, but these are housed in one-size-fits-all, barely customisable prefabricated “exhibits”, which I found pretty, but completely underwhelming. Still, given Frontier’s approach to DLC, I’ve got a private hope they’ll be willing to sell me aviaries, aquariums and proper reptile house capability at a later date. Please, Frontier, let me have the fish. Pretend I am a cute seal if you need to; just get them in my life.

Of course, just because there aren’t many creepy crawlies in the game, it doesn’t mean you won’t find any bugs in your zoos. The beta’s issues with monstrous keepers who refused to feed animals are fixed, and the game was patched significantly even during the review period. Nevertheless, there are still plenty of moments of faint jank, and the potential for serious weirdness – at one point, I had to abandon a zoo because a lemur had escaped thirty feet into the air and was hovering, shrieking at the guests, beyond the reach of any mortal vet, and tanking my framerate in the process.

Admittedly though, serious borkages are rare, and the more I played, the more I found that stuff that seemed broken was actually a result of my own failure, or the occasional failure of the game to explain its own systems clearly. I don’t blame it in that regard – it’s a complex simulation, and there’s a lot to get across to players.

The campaign-ish “career” mode, which is mostly a tutorial, is very thorough, but it’s very hand-holdy too. You’re micromanaged through every button click by a delightful Welsh lady, and once you’ve been pointed through the series of windows you need to visit in order to manage a task, it’s up to you to remember the sequence. The lessons it repeats are the ones that are easiest to learn (move the animal to the habitat! Make the vet research elephant bum disease!), and despite how much I loved listening to my new Welsh aunt, it’s long, to the point where I gave up a third of the way in because I wanted to start my own operation from scratch.

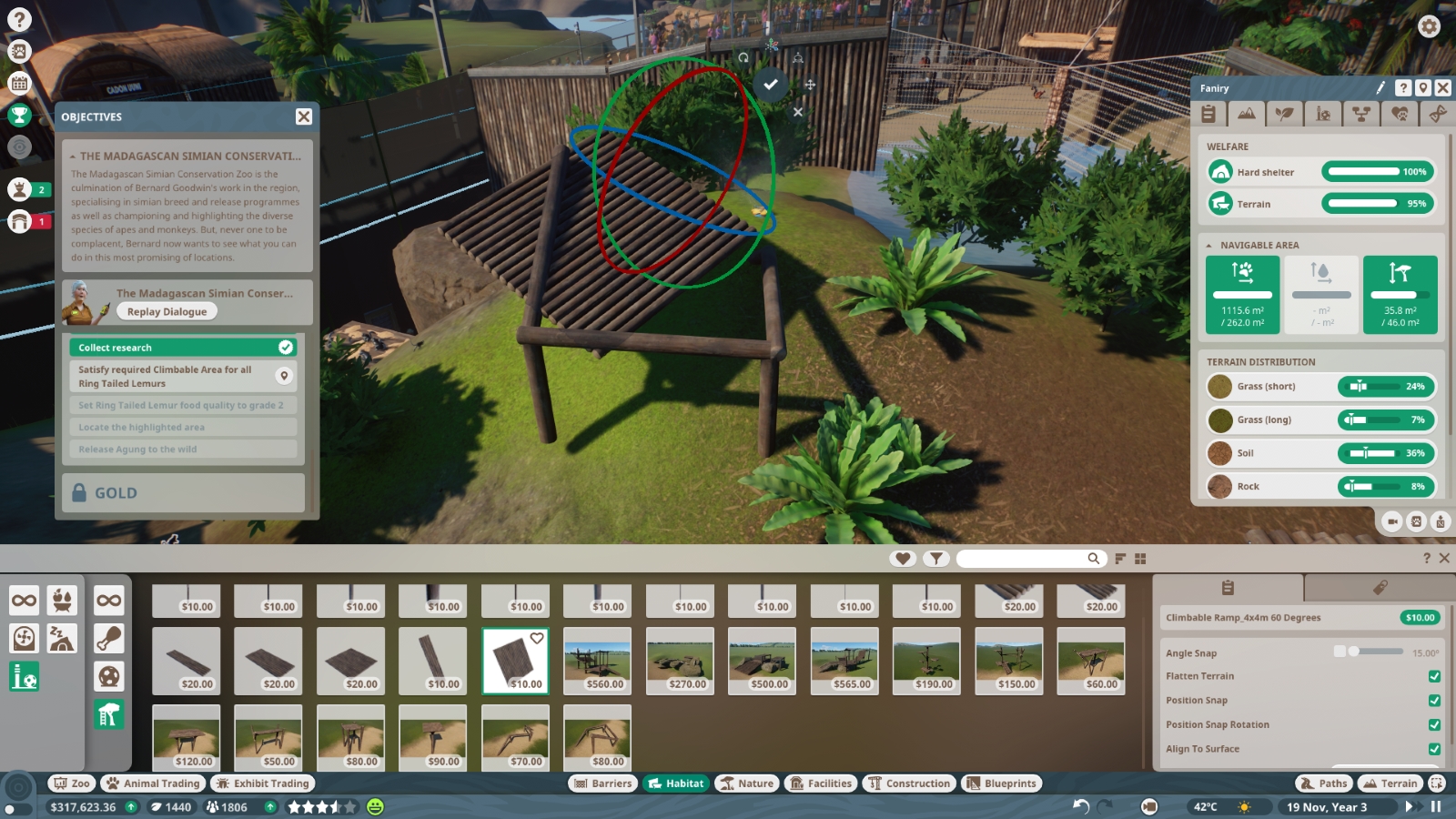

It was when I did, however, that I properly fell in love. You see, Planet Zoo is an utterly phenomenal landscaping construction game, and would be a triumph even if its animals were just farting pixels. Of course, they’re not: the animals are profoundly beautiful. They’re delightfully real, too – they genuinely feel like simulated living things that make their own decisions about how to spend time, and you will want to frequently down tools in order to watch them lumber around shouting at each other. But it really says something that I want to rush past discussing that whole central pillar of the game, and rave about the construction system.

This was my practice map, where I taught myself the terrain tools. Would have paid a tenner just for this, to be honest.

I know a lot of the Planet Zoo’s building tools have been borrowed and adapted from Planet Coaster. But I can’t tell you what’s been carried across, or what’s been improved, because I’ve not played Planet Coaster. I presume it’s a game where you find young, injured rollercoasters in the woods and nurse them back to health, growing them into sixteen-loop behemoths before releasing them onto their own planet. I’ve not played Jurassic World Evolution either, which I also gather was borrowed from. As such, I can only talk about these systems as if they sprung, fully-formed into reality, like Athena from the temple of Zeus, or a gangly baby giraffe from the bum of a larger giraffe.

Starting with a flat plot of land in franchise, challenge or sandbox mode, you can make anything. I really mean that. You are a god, with four vast and terrible hands: the terrain modification tool, the path-making tool, the habitat barrier tool and the construction tool. They take some getting used to, and if you have an eye for detail they can consume you – when I started my first franchise, “St. Beef’s Zoos for the Brave”, I genuinely spent fifteen hours of landscaping, starting anew and landscaping again before I even bought my first St. Beast. But once you’ve developed an instinct for the tools, you’ll find that every time you wonder “wait, could I do… that?”, the answer from the game is a benevolent wink as it offers you a hypothetical shovel.

My first proper zoo, Brute Mesa, was built in the North American desert – I laid down a series of towering buttes and rounded plateaus, linked by soaring rock arches and sheltering pools of warm, crystal-clear water. This would be a vertical zoo, with guest walkways sweeping over terraced enclosures and crocodile-haunted canyons, and arcing round gracefully to connect with the viewing areas of mesa-top enclosures.

Staff facilities would be concealed artfully in caves within the heart of the massifs, while habitats would be decorated with banks of arid scrub, lush vegetation around water sources, and rock piles arranged with karesansui grace. Seriously, I spent hours and hours just rotating and tilting pebbles, until they looked exactly as I wanted them to. I can’t even begin to explain the possibilities offered by how granular the game’s piece-by-piece construction system is – but you’ll find Youtube is rife with people making the most astonishing structures from basic components.

Of course, I got a bit carried away. When I actually bought all the staff facilities I needed to run the zoo and was ready to open, I only had enough money to afford a single Aardvark, called Hasan. I then spent an hour making a wooden shelter for Hasan from individual logs, before enrobing it in grass-speckled earth like a sort of veldt hobbit-hole. When he curled up on the straw under its eaves, cooed over by my first busload of visitors, I felt pure satisfaction.

Brute Mesa at the end of its fifth year in business – and I’ve still only made four enclosures. They look bloody great though.

Of course, it all went tits up after that. I’m having to fight my own hands not to turn this into a diary piece (I will one hundred percent be writing diary pieces about this game), but suffice to say I was taken aback by just what an uncompromising management game this is. And I say this as someone who is, by all accounts, pretty good at management games. Partly, the difficulty was down to the fact I’d near-bankrupted myself building my platonic vision of the American southwest, and partly it was down to the fact the game doesn’t do much to help you manage your money – it doesn’t break down daily costs as transparently as I would like, and there are crucial facts (for example, food stalls aren’t cost-efficient until you have 500-plus visitors per day), that you can only learn through trial and error, or by forum-crawling.

Mostly though, the game is just pleasingly, old-fashionedly challenging, in a way that belies its cutesy exterior. Take out too many loans, and you will be properly monstered by the interest payments. Expand too quickly, or give your animals everything they want straight away, and you will hemorrhage cash. Researching the enrichment bits you’ll need to make animals happier and make more complex enclosures costs vet time, and vets – as cat owners will know – will rinse you.

Staff costs in general are punishing, meaning you have to think very hard about spatial arrangement of facilities, work area assignment, and maintenance rotas in order to make efficient use of your personnel. To make matters more exquisitely complex, you’re balancing this with meeting the needs of your animals, meeting the needs of your guests, and meeting your own overriding aesthetic objectives.

The multiple-axis problems this creates are nicely juicy to solve. Say, for example, you have a savannah enclosure populated by Ostriches and Warthogs. First, the animals have slightly different requirements for feeding, shelter, vegetation and the like, which you have to balance within the one habitat. Then, you realise that if you lump it into the same work group as the Komodo dragon enclosure, the keeper assigned to that will get overworked.

So you decide it’ll need its own food prep shed – and the guests won’t want to see that. But in order to conceal that from view, you’ll need to reduce the amount of pathside glass viewing area. But then, it’ll be harder for the guests to see the animals. You scratch your head, and then grin, as the answer comes to you. You’ll build a gorgeous, arcing elevated walkway over the whole thing, so people can marvel at the ostriches – those wonderful, pin-headed bastards – from above. And that walkway could connect to this rocky outcrop, where you could dig out the space for a series of hyena caves in the cliffs… but they’ll need keeper access. And so it goes on, deliciously.

Of course, it didn’t pan out that way for Brute Mesa. I ended up fifty grand in the hole, having to store the komodo dragon in a wooden crate because I’d been forced to demolish half its exhibit, as it was the only place I could move the water treatment plant without spending money I didn’t have. The water treatment plant needed to be moved because the saltwater crocodile was fed up of wallowing in its own shit. But it was broken anyway. And the mechanics were busy frantically repairing the site of a catastrophic warthog escape. And Hasan, my beautiful Hasan, was the subject of a protest, because the harrowed, underpaid staff hadn’t fed him in days. God bless this mess.

Hasan on hunger strike, with protesters in the background. In the distance, a sign hanging from a rock arch proclaims the name of “Chief Beef” – it’s the name of an in-universe burger franchise, but I like to put the signs around the place at random, as if in celebration of a chilling dictator with burgers for hands.

Alas, It was time to let the sun set on this lovely mess, and start again, on another sprawling patch of land where anything, once again, would be possible. It will take every ounce of my limited self-control not to fire up the game and do exactly that, the moment I hit publish on this review. You should go and do the same.